COPYRIGHT © INHIST.COM / 2023

Mount St Helens: Before and after in photos

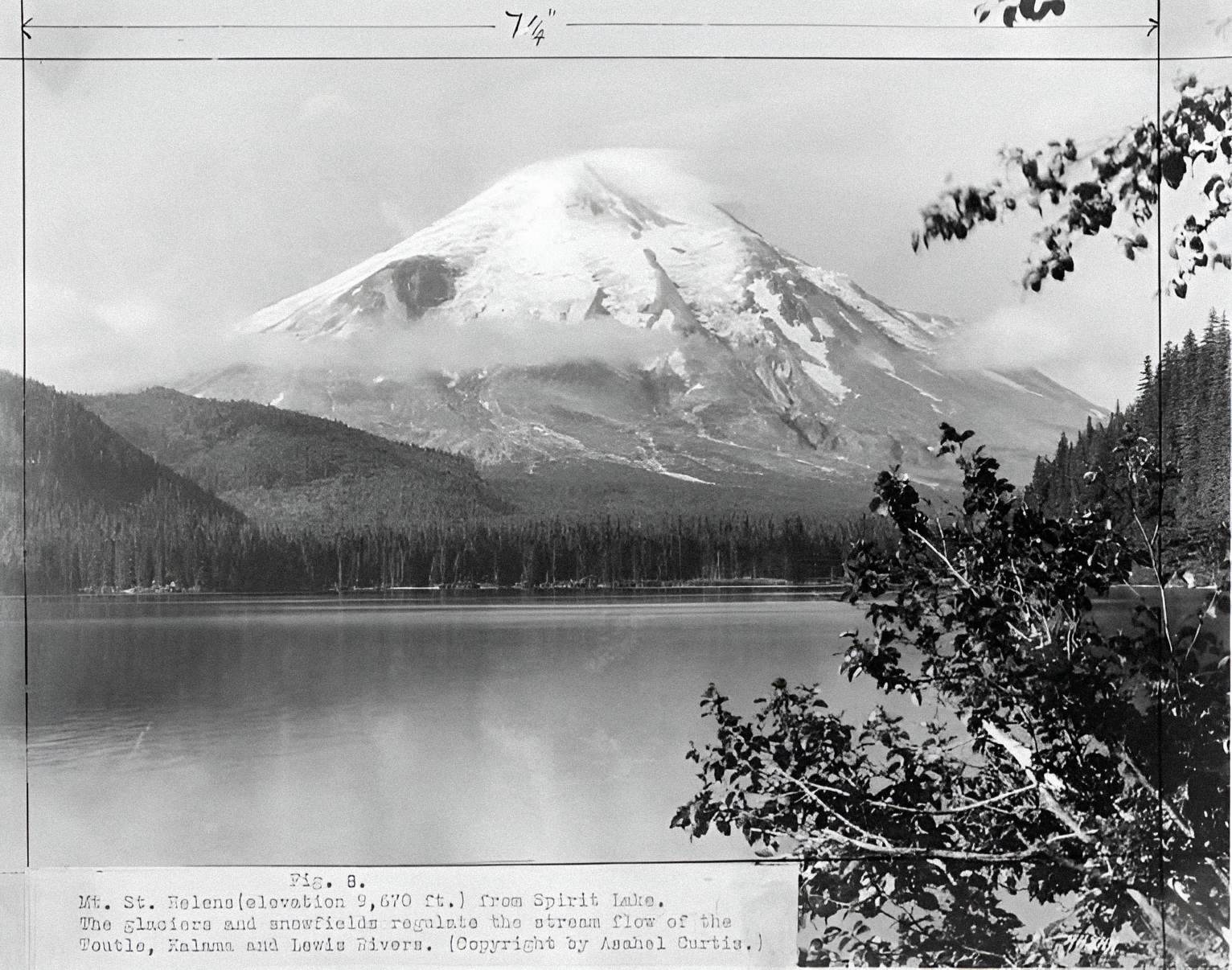

Mount St Helens, located in southwestern Washington, was once a majestic symmetrical cone towering at 9,600 feet above sea level. However, everything changed on May 18, 1980, when the volcano unleashed a catastrophic eruption, leaving a horseshoe-shaped crater and a barren wasteland. This historic event, considered the most disastrous volcanic eruption in United States history, forever altered the landscape and had a significant impact on the surrounding environment and communities.

Pre-eruption signs

In the months leading up to the eruption, Mount St Helens exhibited several warning signs of an impending disaster. A series of earthquakes and steam-venting episodes occurred, caused by the injection of magma at shallow depths below the volcano. This activity created a large bulge and a fracture system on the mountain’s north slope. Geologists and volcanologists closely monitored these seismic activities, trying to predict the volcano’s behavior.

The eruption begins

On March 27, 1980, after weeks of increasing seismic activity, Mount St Helens produced its first eruption in over 100 years. Steam explosions blasted a crater through the volcano’s summit ice cap, covering the surrounding area with dark ash. The eruption intensified over the following weeks, with the crater growing larger and two giant crack systems appearing on the summit area.

It was devastating!

The fateful morning of May 18, 1980, dawned warm and sunny in southwestern Washington. At 8:32 a.m., seismic instruments in the area detected intense shaking. USGS geologists stationed in Vancouver witnessed the seismic activity and realized that something catastrophic was happening at Mount St Helens. They quickly mobilized to gather data and assess the situation.

A fire-spotter plane was dispatched to investigate, and what the crew saw was both awe-inspiring and terrifying. The volcano’s top had been completely blown off, replaced by a gray columnar cloud that reached a staggering height of over 80,000 feet. Within the cloud, lightning flashed, and the margin of the column was composed of convecting cells. Pyroclastic flows were observed moving northward, causing further destruction in their path.

Immediate aftermath

The immediate aftermath of the eruption was chaotic and devastating. The ash column darkened and intensified, spreading ash and volcanic gas across a wide area. The Toutle River valley experienced massive mudflows, known as lahars, as snow and ice on the volcano melted rapidly. These lahars reached as far as the Columbia River, causing extensive damage and altering the landscape.

Tragically, the eruption claimed the lives of 57 people, including geologist David A. Johnston who was stationed at Coldwater 2, an observation post near the volcano. Johnston’s final moments were captured in a radio transmission he made just before the eruption engulfed him. The eruption also caused billions of dollars in damage, destroyed thousands of acres of land, and left a massive crater on the north side of Mount St Helens.

Environmental impact

The environmental impact of the Mount St Helens eruption was profound and far-reaching. The blast and subsequent pyroclastic flows stripped vegetation from the landscape, leaving behind a barren wasteland. Entire forests were flattened, and over four billion board feet of timber were destroyed. The lahars that flowed down the Toutle River valley carried massive amounts of sediment, burying entire ecosystems and altering river channels.

Despite the devastation, life began to slowly return to the area. Within a few years, plants colonized the barren land, and animals started to repopulate the region. Scientists closely monitored the recovery, studying the resilience of nature and the processes of ecological succession. Today, the area is designated as the Mount St Helens National Volcanic Monument, serving as a living laboratory for researchers studying the long-term effects of volcanic eruptions.

Impact on communities

The eruption of Mount St Helens had a profound impact on the surrounding communities. Towns and cities were covered in thick layers of ash, causing widespread disruption and health hazards. The ashfall damaged crops, contaminated water supplies, and disrupted transportation systems. Residents had to wear masks to protect themselves from the fine particles, and cleanup efforts took months, if not years, to complete.

The eruption also led to changes in land ownership. Prior to the eruption, the summit of Mount St Helens was owned by the Burlington Northern Railroad. However, after the eruption, the land was transferred to the United States Forest Service, which later established the Mount St Helens National Volcanic Monument to preserve and study the area.

Lessons learned and ongoing monitoring

The eruption of Mount St Helens served as a wake-up call for the scientific community and the public. It highlighted the importance of monitoring and studying volcanoes to better understand their behavior and mitigate the risks associated with volcanic eruptions. Today, advancements in technology allow scientists to closely monitor volcanic activity, providing early warning systems and valuable data for eruption predictions.

Satellites in orbit and scientists on the ground continue to monitor Mount St Helens, tracking its ongoing recovery and any signs of future volcanic activity. The knowledge gained from studying Mount St Helens has not only improved our understanding of volcanic processes but has also contributed to the development of strategies for mitigating the impacts of volcanic eruptions worldwide.

Final words

The eruption of Mount St Helens on May 18, 1980, forever changed the face of the famous volcanic peak. What was once a snow-capped beauty became a smoldering crater and a symbol of both destruction and resilience. The event taught us valuable lessons about the power of nature and the importance of preparedness. Today, Mount St Helens stands as a reminder of the ongoing forces shaping our planet and the need for continued scientific inquiry and vigilance in the face of volcanic activity.